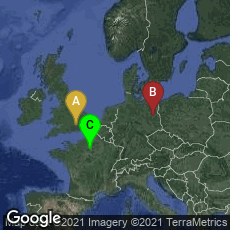

A: London, England, United Kingdom, B: Bezirk Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, Berlin, Berlin, Germany, C: Paris, Île-de-France, France

Modern replica of the Staffelwalze, or Stepped Reckoner, a digital calculating machine invented by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz around 1672 and built around 1700, on display in the Technische Sammlungen museum in Dresden, Germany. It was the first known calculator that could perform all four arithmetic operations; addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. 67 cm (26 inches) long. The cover plate of the rear section is off to show the wheels of the 16 digit accumulator. Only two original machines were made, of which he single surviving prototype is in the National Library of Lower Saxony (Niedersächsische Landesbibliothek) in Hannover.

In 1673 German mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz made a drawing of his calculating machine mechanism. Using a stepped drum, the Leibniz Stepped Reckoner, mechanized multiplication as well as addition by performing repetitive additions. The stepped-drum gear, or Leibniz wheel, was the only workable solution to certain calculating machine problems until about 1875. The technology remained in use through the early 1970s in the Curta hand-held calculator.

Leibniz first published a brief illustrated description of his machine in "Brevis descriptio machinae arithmeticae, cum figura. . . ," Miscellanea Berolensia ad incrementum scientiarum (1710) 317-19, figure 73. The lower portion of the frontispiece of the journal volume also shows a a tiny model of Leibniz's calculator. Because Leibniz had only a wooden model and two working metal examples of the machine made, one of which was lost, his invention of the stepped reckoner was primarily known through the 1710 paper and other publications. Nevertheless, the machine became well-enough known to have great influence.

Leibniz conceived the idea of a calculating machine in the early 1670s with the aim of improving upon Blaise Pascal's calculator, the Pascaline. He concentrated on expanding Pascal's mechanism so it could multiply and divide. The first recorded indirect reference is in a letter from the French mathematician Pierre de Carcavi (Carcavy) dated June 20, 1671 in which Pascal's machine is referred to as "la machine du temps passé." Leibniz demonstrated a wooden model of his calculator at the Royal Society of London on February 1, 1673, though the machine could not yet perform multiplication and division automatically. In a letter of March 26, 1673 to Johann Friedrich, where he mentioned the presentation in London, Leibniz described the purpose of the "arithmetic machine" as making calculations "leicht, geschwind, gewiß" [sic], i.e. easy, fast, and reliable. Leibniz also added that theoretically the numbers calculated might be as large as desired, if the size of the machine was adjusted; quote: "eine zahl von einer ganzen Reihe Ziphern, sie sey so lang sie wolle (nach proportion der größe der Maschine)" ("a number consisting of a series of figures, as long as it may be in proportion to the size of the machine").

On July 14, 1674, Leibniz informed Heinrich (Henry) Oldenburg, secretary of the Royal Society, that a new model had "at last been successfully completed" and was able to "produce a multiplication by making a few turns of a particular wheel, without any effort." The letter also refers to his good fortune in being able to entrust the work to the Parisian craftsman and clockmaker Olivier (or Ollivier: his first name does not seem to be known), ‘a man who preferred fame to fortune’ (quoted in M.R. Antognazzi. Leibniz: an intellectual biography [2009]). Leibniz showed off an improved version of the calculating machine at the Académie royale des sciences in Paris on January 9, 1675, and on his final departure from Paris on October 4, 1676 took a further improved model to show Oldenburg in London.

After Leibniz’s departure, work on the calculating machine continued under the supervision of his Danish friend Friedrich Adolf Hansen (1652-1711), and Leibniz continued to correspond with Olivier. The Leibniz archive includes three letters from Olivier, dated March 24 and July 29, 1677 and November 15, 1678; indeed Leibniz seems to have had some effort made to have Olivier called to Hanover to continue his work. After about 1678 work on the machine seems to have lapsed until Leibniz began to develop a new prototype in the early 1690s. At some point Leibniz's wooden model and his first metal machine were lost. The second machine, which was built from 1690 to 1720, is preserved in the Niedersächsische Landesbibliothek, Hanover.

On May 21, 2014 Christie's in London auctioned Leibniz's autograph draft contract between Leibniz's friend Adolf Hansen, acting on Leibniz's behalf and the clockmaker Olivier in Paris, for the construction of Leibniz's calculating machine. The 3.5 page contract written by Leibniz in French consisted of 20 numbered articles with some details of payments left blank. The contract was undated but Christie's assigned to it the date of circa 1677. The manuscript came "from the collection of the French Leibniz scholar Lous-Alexandre Foucher de Careil (1826-1891) -- by descent – private collection."

From Christie's catalogue description I quote:

"‘Le dit sieur Leibniz m’ayant informé partie par écrit, et partie de vive voix et par quelques modelles, d’une machine Arithmetique de son invention; en sorte que je n’y ay trouvé aucune difficulté, je me suis engagé à l’executer de la manière suivante …’

"The contract comprises 20 meticulously detailed clauses, describing in detail the machine and the financial and practical arrangements for its construction: it is to produce numbers up to three figures; it is to be capable of multiplication and division, as well as addition and subtraction, with the mechanism (consisting of a system of fixed and mobile pieces, and equal and unequal cogs) described in detail, first for multiplication and division, then for addition and subtraction, noting that the operations should be effected immediately ‘et non pas comme dans la machine du temps passé après un delay ou intervalle’; the machine is to be perfectly finished, made of iron or steel, and enclosed in ‘une petite boëtte propre, à fin qu’il ne paroisse que ce qu’il faut pour l’opération’; the operation of the machine is then specified. The contract goes on to note that Olivier had previously agreed to construct such a machine in one or two months for a payment of ‘cent écus blancs ou trois cens francs’, part of which has been advanced, but that he had failed (in part because of illness) to give satisfaction; he now engages to complete the work in three months, with his goods as surety; and he is to show the progress of his work to Hansen, and inform Leibniz by letter, each week.

"‘La machine doit avoir deux pieces aussi longues qu’elle, dont l’une est immobile et sert de base à tout, l’autre est mobile, et glisse dans la première, à fin d’aller de chiffre en chiffre lors qu’on change les multiplicateurs ou les quotiens de la division …

"La piece mobile porterà ce qui sert pour le nombre qui doit estre multiplié et pour le nombre qui doit estre divisé: au lieu que la precedente servoit pour le produit, pour le multipliant, et pour le quotient cellecy portera donc les roues à dens inégales, et ce qui sert à les ajuster, et à les mettre sur un nombre donné, afin que tantost 9, tantost 8, tantost 7 dens inegales rencontrent la roue de la partie immobile qui y repond …’ "

Christie's estimated the contract at £200,000-£300,000; however, the manuscript did not sell in the auction.

(This entry was last revised on 07-26-2014.)