Portrait of Koenig's patron printer Richard Taylor from Brock & Meadows, The Lamp of Learning: Taylor & Francis and the Development of Science Publishing (1984).

Portrait of Koenig's patron printer Thomas Bensley from Brock & Meadows, The Lamp of Learning: Taylor & Francis and the Development of Science Publishing (1984).

Sheet H (on the right) printed in April, 1811, was the first printing done by a Koenig power press. Note the different ink color and presswork from the previous sheet (on the left).

"Friedrich Koenig and the Cylindrical Press". Painting by Douglas M. Parrish in the series Graphic Communications Through the Ages preserved in the Cary Graphic Arts Collection, Rochester Institute of Technology.

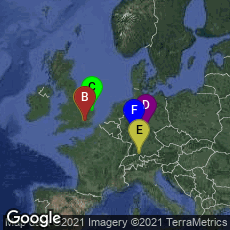

A: London, England, United Kingdom, B: London, England, United Kingdom, C: Norwich, England, United Kingdom, D: Suhl, Thüringen, Germany, E: Oberzell, Ravensburg, Baden-Württemberg, Germany, F: Innenstadt I, Frankfurt am Main, Hessen, Germany

At the beginning of the 19th century, a time of unprecedented advances in the application of machinery to many forms of production, printing retained elements of a traditional handcraft. All printing was still done on hand presses, the output of which remained 200-250 copies per hour, a rate essentially unchanged since the invention of printing in the second half of the 15th century. To produce daily newspapers with larger circulations pressmen operating several hand presses working in tandem for long hours could produce several thousand copies per day. For larger editions of books or weekly magazines stereotyping, as it became increasingly adopted during the first decades of the 19th century, speeded up hand press output by eliminating the need for repeated typesetting when a book or magazine was printed on multiple hand presses working in tandem. But for daily newspapers, some of which issued several editions per day, the limitations of hand press printing placed a cap on circulation, especially since the large sheets used for newspapers were twice the size of the platen on most models of the popular Stanhope iron hand press, requiring two pulls to take one side through that press. As production processes of many kinds were mechanized, causing production in various industries to increase during the Industrial Revolution, there was a particular incentive in the publishing industry to mechanize and speed up the printing of newspapers and magazines in order to increase circulation.

In the early years of the nineteenth century, around 40 years after James Watt made the steam engine practical, engineers in England obtained sufficient control over steam to develop small stationery steam engines, generally of one or two horsepower, that could power small industrial facilities such as printing presses. The first table engine was developed in England by James Sadler in 1798; it was greatly improved and patented by Henry Maudslay in 1807. Steam engines of similar design, but different sizes, would power printing machines for much of the nineteenth century. Even though we correctly associate the steam engine as powering the Industrial Revolution, for most of the Industrial Revolution the majority of small machines were driven by wind and water power, as well as horse and man-power rather than steam. This explains why several of the early rotary or machine presses were designed to be driven by alternative power sources: horse, or human power rather than steam engines. Others could be driven by human power if a steam engine was non-operational.

Mechanization of printing through a steam-powered cylinder press was first accomplished in London by printer and inventor Friedrich Koenig (König) in a series of inventions between 1810 and 1814. A native of Suhl, Germany, Koenig had designed a power-driven device known as the Suhl press around the year 1803. Whether he built an actual machine at the time is unknown. In order to develop his invention Koenig moved to London because Germany lagged behind Great Britain in the Industrial Revolution, and Koenig found no backers for the development of his printing machine in Germany. In his account of the development of the power press published in The Times newspaper on December 9, 1814 Koenig also emphasized that lack of an adequate patent system was a major factor contributing to the delay of industrial development in Germany.

By this period in the Industrial Revolution the disruptive social and economic impacts of the factory system were being felt increasingly by the working classes of England, causing widespread resentment against the replacement of traditional handcrafts by machinery. Most famously, while Koenig was developing his machines in London the Luddite machine breaking-riots against power looms in the textile industry occurred in the manufacturing districts of England in 1811 and 1812, with the trials and conviction of most of those accused in 1812 and 1813. Hand press printers in London would express resentment toward the new printing machinery, though, unlike the Luddites, they did not break printing machines.

In London Koenig was introduced to Thomas Bensley, a printer interested in innovative technology. Bensley brought in two other printers, George Woodfall and Richard Taylor, to help finance the development of Koenig's powered press. In England it was understood that William Nicholson had patented the general concept of the cylinder press in 1790, but also that Nicholson had never actually built a press. At some point in his inventing process Koenig undoubtedly benefitted from reading Nicholson's patent, though after Koenig succeeded Nicholson never asserted a prior claim to the invention. Koenig would have had ready access to the publication of Nicholson's patent in The Repertory of Arts and Manufactures, Number xxvii, Vol. 5 (1796) 145-170.

With the support of his backers Koenig was able to proceed with development of the printing machine, and received his first British patent No. 3321 on March 29, 1810 for "A Method of Printing by Means of Machinery," describing his powered platen press. The expression "Printing by Means of Machinery" in the title of Koenig's patent was the first time that a printing press was referred to as a machine since the wording of William Nicholson's 1790 patent: "A Machine or Instrument on a New Construction for the Purpose of Printing...." Moran described Koenig's first printing machine this way:

"The inking apparatus consisted of several cylinders vertically arranged, above which was an ink-box, through a slight in which the ink was forced by a piston to fall on the cylinders, by which it was distributed. These cylinders were perforated brass tubes, through the axles of which, also perforated, steam or water was introduced to moisten the felt or leather covering. Koenig and Bauer, unlike Nicholson, gave detailed detailed specifications of the 'mill work' which carried the carriage backward and forward and depressed the platen. This operation was accomplished by a compound lever causing a screw to make a quarter of a revolution. The tympan was raised and thrown back, as the carriage left the platen, by a chain attached to the end, while a bar depressed it into position again as the carriage returned. The frisket, instead of being hinged to the free end of the tympan—as in the hand press—sprang up by the action of counterweights the moment the tympan was thrown back, thus released the sheet of paper, which was changed by hand. The press is said to have worked at the rate of 800 impressions an hour—a great advance on the hand press—but it was really a dead-end; it could advance no further technically, and the inking apparatus was considered unsatisfactory" (Moran, Printing Presses, p.105)

In April, 1811, at Richard Taylor & Co. Printers in Shoe Lane, London, Koenig conducted the first test of his steam-driven platen press, printing 3000 copies—a relatively large edition for the time— of sheet H (pp. 113-128) of The New Annual Register, or General Repository of History, Politics, and Literature for the Year 1810. This was the first printing done by the first printing press not powered by hand, and, at the rate of 800 sheets per hour, it achieved more than double the speed possible with an iron hand press, such as the Stanhope press. Comparing the press work on sheet H with the sheets in the rest of the complete volume of the Register for 1810 in my collection, it is evident that the printing of this experimental sheet is different, and perhaps inferior.