Both of these copies of the first and second editions are in presentation bindings of morocco leather.

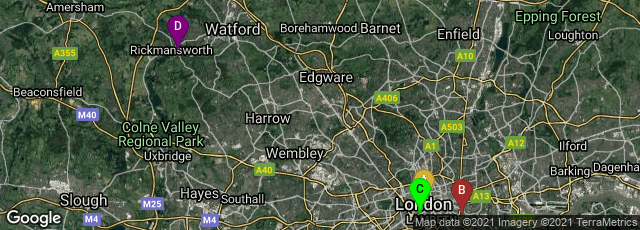

A: London, England, United Kingdom, B: London, England, United Kingdom, C: London, England, United Kingdom, D: Rickmansworth, England, United Kingdom

On April 28, 1800 Pomeranian-English papermaker Mathias Koops was granted English patent no. 2392 for Extracting Ink from Paper and Converting such Paper into Pulp. Within the patent Koops described his process as "An invention made by me of extracting printing and writing ink from printed and written paper, and converting the paper from which the ink is extracted into pulp, and making thereof paper fit for writing, printing, and other purposes." This was the first patented process for recycling paper, and it is also possibly the first patent received for a recycling process that was— much later— widely used. Koops patented his process with the expectation of providing an alternative source of high quality paper at a time when the traditional source of paper--linen rags--were in short supply at relatively high cost.

Also in 1800, with the expectation of producing new paper from materials previously not utilized for the purpose, Koops published the first edition of Historical Account of the Substances which Have Been Used to Describe Events, and to Convey Ideas from the Earliest Date to the Invention of Paper — a serious account of the history of materials used for recording information. Koops published this work to promote his extremely ambitious venture to produce paper from materials other than linen rags— The Straw Paper Manufactory, and it is likely that he presented most copies to potential investors in that project. For that reason Koops had the first edition of his book printed entirely on yellow paper made from straw. The following year he had part of the expanded second edition, the text of which was essentially identical to the first, printed also on straw, but he also had a portion of the second edition printed on recycled paper, with the exception of the frontispiece image of the papyrus plant, which was printed on straw in both versions of the second edition. Koops characterized this recycled paper as "Printed on Paper Re-Made from Old Printed and Written Paper." The paper used was of the wove type, without any watermarks. The copies printed on recycled paper were the first books ever printed on recycled paper, and may have remained the only books printed on recycled paper for a century or more; I have been unable to find any study of this topic.

The appendix of all copies of Koops's second edition (pp. 259-73) was printed on paper made from wood pulp. Printing on paper made from wood fibers may have been first shown in Jacob Christian Schaäffer's Versuche und Muster ohne all Lumpen oder doch mit eniem geringen Zusatze derselben Papier zu machen (1765-71), and it is probable that Koops got the idea for producing this paper from Schäffer's work. My copy of the 1801 edition of Koops's book shows that his recycled paper was of excellent quality; his wood pulp paper somewhat less so, since that final gathering of my copy has browned but remains sound.

From the name of Koops's enterprise—The Straw Paper Manufactory— it is evident that he considered the production of paper from materials other than linen rags to be more commercial than the paper recycling process he invented. One of his patents for the production of paper of this type was "Manufacturing paper from straw, hay, thistles, waste and refuse of hemp and flax, and different kinds of wood and bark. British Patent number 2481 published 17 February 1801."

The scale of Koops' manufacturing scheme was extraordinarily large and expensive for the time. Koops was also a gifted promoter of his project, and the shortage of rags for paper production was well-known enough that Koops was able to raise a very large amount of capital for the venture.

In order to accept money from more than five investors Koops had to petition parliament to pass the Koops Papermaking Patent Act 1801. That parliament would pass a law to assist Koops in developing his papermaking business suggests government recognition of its strategic value, or perhaps just the greed of well-placed investors who were sure that Koops had discovered "the next big thing." The act permited the Koops patent to be held by up to sixty people, and allowed Koops to sell stock and build his large paper making factory of at Millbank. Details of Koops' petition were printed in Report on Mr. Koops' Petition, Respecting his Invention for making Paper from various Refuse Materials...Ordered to be printed 4th May 1801:

"Then John Hunter, Esquire, being examined, said, That to carry on the Manufacture mentioned in the Petition, would require a Sum of Money far beyond the Means or Power of the Petitioner to bring foward, and that he knew several Gentlemen who were ready to hazard and subscribed nearly One Hundred Tousand Pounds for the Purpose of establishing and carrying on the said Manufacture, on being permitted to participate in and enjoy the Liberties and Privileges granted to the Petitioner by the said Letters Patent; but that no Five Persons would forward to hazard such a sum.

"Then Mr. John Rennie, an Engineer, being examined, said, That the Works necessary and alread ordered to be built for the Purpose of carrying on the said Manufacture, together with the Steam Engine, Utensils, and Machinery, will cost about £50,000.

"Then Mr. Benjamin Cooper, a Surveyor, being examined, said, That he had prepared Plans for the different Buildings necessary for carrying on the said Manufacture, the Expense of which Buildings will cost about £50,000.

"Then Mr. Elias Carpenter, Paper Maker, being examined, said That not less than Five Hundred Persons would be employed in the first Instance in the said Manufacture; and on the Sale on which it was proposed to establish it, he believed not less than Eight Hundred or One Thousand Persons would be necessary: that Three Fourths of the Rags consumed in this Country is supplied from Abroad, which by this Manufacture would in a great Measure be rendered unnecessary; and that he has not the least Doubt but that this Manufacture, if established, will considerably reduce the Price of Paper, as it can be carried to any Extent; that the Scarcity of Rags has been so great as to prevent the Paper Makers from executing their Orders at any Price, and the Buyer would have been a Loser if he had taken the Paper at even half the advance Price the Paper Maker could have afforded to sell it at. He produced to Your Committe several Samples of Paper, which were made by him under the Direction of the Peititioner, and which were made solely from Straw and Wood, without the Mixture of any other article.

"Mr. Thomas Burton, Printer to the Tax Office, being then examined, said, That in July 1799, he had not less than Three Presses standing still for the Want of Paper...."

The best historical account of Koops' overly ambitious and dramatically unsuccessful Straw Paper Manufactory that I read appeared, unexpectedly, in a book of studies on the artist and poet William Blake, even though the connection of Koops to Blake is very tangential: Keri Davies, "William Blake and the Straw Paper Manufactory at Millbank," pp. 233-261 in Blake in Our Time: Essays in Honour of G.E. Benley Jr., edited by Karen Mulhallen, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010).

". . . By 1800 Koops had experience of manufacturing from waste paper at Neckinger mill in Bermondsey, . . .

"Having proved the possibility of making good paper from such materials, Koops set up a company, the Straw Paper Manufactory, raised over £70,000 by issue of shares, and in 1801 erected a paper-making mill at Millbank in Westminster. Contractors for the machinery included John Rennie, the engineer, and the firm of Boulton and Watt. This paper mill was easily the largest in the country. The enterprise, however, was over-ambitious and under-capitalized. Koops himself was the principal shareholder in the venture and on the strength of this offered to satisfy his creditors. His failure to discharge his bankruptcy by 1802 compelled Koops's creditors to issue a writ, inter alia, for seizure of the Straw Paper Manufactory's assets, and in the end its proprietors could not keep the enterprise solvent. The Millbank paper mill and its equipment were eventually offered for sale by auction in October 1804, thereby ending the possibility of England challenging the European paper industry by using more easily available materials for making paper" (Oxford DNB).

____________

As I indicated above, I have been unable to find any thorough study of the earliest history of recycled paper, or of Koops's business activities, and it is probable that most of the history may remain unknown. However, on April 12, 2014 I received an email from my friend and colleague Ove Hagelin in Stockholm, which may provide a clue to elements of the history previously unrecorded. Ove Hagelin wrote:

"When cataloguing the odontological collection at the Hagströmer Library I found this very special edition of a popular dentistry book that may be of interest for paper historians:

"RUSPINI, Bartholomew.

A Treatise on the Teeth: Wherin an Accurate Idea of their Structure is given, the Cause of their Decay Pointed out, an their Various Diseases enumerated; to .which is added, the most effectual method of treating the Disoriders of the Teeth and Gums, established by a long and successful Pratcice, by the Chevalier Ruspini, . . . The Tenth Edition + (with separate title-leaf) A Concise Relation of the Effects of an Extraordinary Styptic lately discovered; in a Series of Letters, from Several Gentlemen of the faculty, abd from the Patients. To Chevalier Ruspini, Surgeon-Dentist to His Royal Highness The prince of Wales.London, printed for the Author, and may be had at his house in Pall-Mall; . . . 1802. (Reynell, Printer, Piccadilly). 8vo - leaf: 192 x 120 mm. Pp iv, 5-52 + (A Concise Relation): pp [53]-128. The first five sheets (A-E4, pp 1-40, are printed on yellow paper made from straw watermarked:

"CHEVALIER RUSPINI

PALL MALL

PATENT STRAW PAPER

"The rest of the book is printed on white paper but at head of page 42 there is a printed rubric reading “Regenerated Paper”, followed by the description of Case 1, dealing with a Lady of Kent., but there is nothing written about the paper.

"I have tried to trace more copies of this “Tenth Edition”, dated 1802, but in vain. The book was very popular and no less than 13 editions appeared between 1768 and 1813. Richard Aspin at Wellcome has checked for me that their 1797 edition is printed on normal rag paper. I have also noticed in the British Library catalogue a copy of the 1780? edition printed on “tinted paper”??