As Herodotus (Ἡρόδοτος) was the founder of historical writing, references to written or archival records in his Histories (The History) are of particular interest. By the mid-fifth century BCE writing in Greece had existed for only about 300 years. Because writing was relatively new, and only a small portion of society was literate, it may not be surprising that Herodotus appears to have consulted few written sources in compiling his Histories. From Herodotus's own account it seems that most often he did not find it necessary, or perhaps practical, to verify information that he compiled from personal observation through the consultation of written records. Herodotus also expected his Histories to be read aloud, in which case citing written sources within the Histories might have been a kind of distraction.

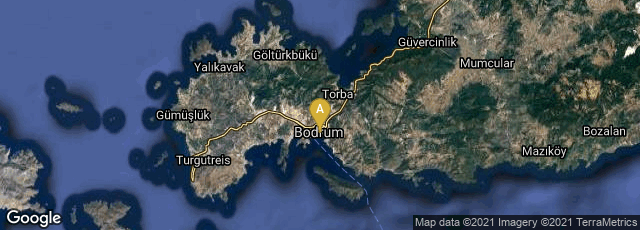

Herodotus begins his Histories with a sentence that has been translated in various ways: "Herodotus of Halicarnassus here presents his research so that human events do not fade with time." Another translation of the same sentence reads, "What follows is a performance of the enquiries of Herodotus from Halicarnassus." According to Robert Strassler, editor of The Landmark Herodotus (2007) 3, Proem.b, "This almost certainly implies that Herodotus performed (read aloud) his text, in whole or in part, to an audience gathered to hear him."

Herodotus usually refers to records in the context of government, law, or communication. He often refers to dispatches sent by leaders as part of political or military negotiations, such as dispatches sent in the context of war. He describes attempts to send secret messages. He also refers to records used for the enforcement of laws, which were, of course, in written form. He is aware of both the advantages and disadvantages of writing over oral communication.

"Herodotus recognized the usefulness of writing for interpersonal communication, but he also knew that it could be problematic. Because writing fixed a message in time and space, a written document that seemed objective and straightforward could also be full of paradoxes. In the generation after Herodotus, Socrates would complain (in the dialogue Phaedrus, set down by Plato) that writing represented 'no true wisdom, . . . but only its semblance.' Written words 'seem to talk to you as though they were intelligent,' the philosopher said, 'but if you ask them anything about what they say, from a desire to be instructed, they go on telling you the same thing for ever.' Even worse, once something is put in writing it 'drifts all over the place, getting into the hands not only of those who understand it, but equally of those who have no business with it; it doesn't know how to address the right people, and not address the wrong. '

"Like Socrates, Herodotus knew that writing was full of ambiguities. Since a written document could not be cross-examined as a speaking person could, it might be used not to inform but to deceive. Themistocles, the Athenian general who led the resistance to the invasion of Xerxes. knew this too. Both sides in the war were vying for the help of the Ionians, descendants of Greek settlers who had colonized the Aegean islands and the adjacent mainland coastal areas of present-day Turkey. Most Ionians sided with the Persians, their powerful near-neighbours, but the Greeks sought their aid on the grounds of common ancestry. Themistocles used the ambiguity of writing to enlist their help, or at least to minimize the potential harm they might do to the Greek cause. He sent men to the "drinkable-water places" where Ionian ships put in for resupply, and he had them cut written messages into the rocks there, urging the Ionians to abandon Xerxes and join the Greek side. His plan was clever: either the Ionians who read the messages would be persuaded to rebel against the Persians, he reasoned, or Xerxes himself would see the messages and distrust his allies, withholding them from the order of battle (8.22). As it happened, only a few Ionians defected to the Greeks (see 8.85), but a more important point had been made: writing could send a deliberately confusing message as well as a direct one. Writing was not always so straightforward as it appeared to be.

"Writing could also be useful for sending messages in secret, and Herodotus provided several examples of how written records promoted secrecy. There was a danger in committing anything to writing since, if the document were intercepted, secrecy would be lost. Histiaeus, who had been made Despot of Miletus by Darius, learned this lesson when he sought through secret messages to stir up a revolt against his benefactor. The King's brother intercepted these letters, read them, and then sent them on to their original destination, having meanwhile profited from knowing what plans were afoot. When the revolt came, the loyal forces 'killed a great number ... when they were thus revealed' (6.4). Still, writing out a message and smuggling it to a confederate could be safer than entrusting it orally to a messenger, who could be bribed or tortured into talking if apprehended. Because of the possibility of such discovery, special care was needed over secret communications, and Herodotus found several instances of such security precautions.

"These stories present the historian at his anecdotal best, and we may well doubt whether any of them actually happened. Their very dramatic content, however, highlights the problem Socrates complained of; namely, writing drifting 'all over the place' and getting into the wrong hands. In one case, a Mede named Harpagus plotted with Cyrus to overthrow the King and install the young man in his place. 'Because the roads were guarded,' a secret message had to be smuggled through by some 'contrivance.' Harpagus took a hare and split open its belly, leaving the fur intact. Next, he inserted "a paper on which he wrote what he wanted," stitched the animal back together, and entrusted it to a servant, disguised as an innocuous huntsman. The servant made it past the guards along the road and delivered the message to its intended recipient (1.123; the text of the message itself is at 1.124)" (O'Toole, "Herodotus and the Written Record," Archivaria 33 [1991-92] 153-54).

Whatever Herodotus's ideas regarding the written record, his Histories survived because he wrote them down, and because they were re-copied. According to Roger Pearse, tertullian.org, 18 papyrus fragments of Herodotus survived, all fragments of a page, with little overlap. Most of these fragments date from the first or second centuries CE. Pearse cites nine medieval manuscript exemplars. The earliest, Laurentian 70, 3, known as Codex A, dates from the 10th century C.E. This was carefully written by two scribes in succession. The text contains marginal summaries and the remains of scholia, copied from its exemplar, as well as much later marginal notes, especially in book 1.

Pearse provides the following general comments on the surviving sources for Herodotus: "The manuscripts and papyri do not give us information on all the forms of the text of Herodotus that were known in antiquity. This we can see from the quotations of the text in other ancient authors.... Both the manuscripts and papyri appear to derive from a common ancient edition which was widely circulated in the early centuries AD. Who made this is unknown...."

(This entry was last revised on 04-24-2014.)