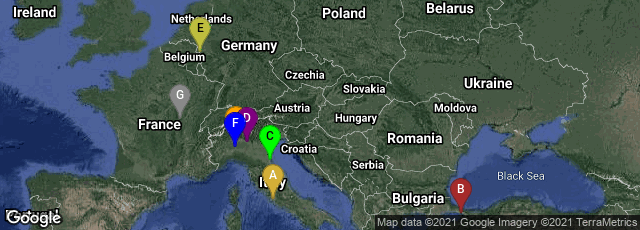

A: Roma, Lazio, Italy, B: İstanbul, Turkey, C: Ravenna, Emilia-Romagna, Italy, D: Brescia, Lombardia, Italy, E: Mitte, Aachen, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany, F: Pavia, Lombardia, Italy, G: Autun, Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, France, H: Monza, Lombardia, Italy

"An interest in classical antiquity never waned altogether during the centuries of the Middle Ages. In the West and particularly in Italy, the great Latin classics never ceased to be studied in the schools and cherished by individuals with a bent for letters. It is true that writers like Tacitus and Lucretius, Propertius and Catullus, just to give a few leading examples, fell quickly into oblivion after the Carolingian age, only to reappear again with the rise of humanism. But Virgil and Cicero, Ovid and Lucan, Persius and Juvenal, Horace and Terence, Seneca and Valerius Maximus, Livy and Statius, and the list is by no means complete, were always read. Virgil became also a prophet of Christianity by the fourth century and a sorcerer in the twelfth century. Some of Ovid's poems were given a Christian interpretation, while Seneca, besides being hailed as the traditional exponent of ancient morality, was also cherished as the correspondent of St. Paul, which he certainly was not. Even after the fall of the Roman Empire, the idea of Rome as 'caput mundi' never faded out in the West. Neither Constantinople nor Aachen ever succeeded in achieving the universal prestige of Rome, just as neither Ravenna nor Antioch, nor Milan, nor Aquileia, nor Treves, had ever come near it during the last centuries of the Empire. The very Barbarians who invaded Italy succumbed to Latin civilization, just as some centuries before the Romans had surrended to that of conquered Greece. Towns were proud of their Roman origins. At Pavia an inscription, testifying to the existence of the town in Roman times, was preserved as a relic in a church, while the equestrian statue of a Roman Emperor, known as the 'Regisol' and removed from Ravenna, adorned one of its squares and was the visible symbol of the town and its traditions until its destruction at the hands of the French in 1796.

"That some interest in the ancient monuments remained alive is not surprising, just as it is not surprising that even smaller antiquities, such as coins, ivories, or engraved gems, were continually sought after during the Middle Ages. 'What was lost, notwithstanding the reminder contained in St. Augustine's Civitas Dei, was the Varronian idea of 'antiquitates'— the idea of a civilization recovered by systematic collection of all the relics of the past.' What led to the collection of antique objects during the Middle Ages was not their antiquity but their appeal to the eye or their rare or unusual materials, or simply because they were different; or even in some cases because they were thought to be endowed with magical powers. The antiques preserved in the treasuries of cathedrals were kept there because their materials or their craftsmanship were considered precious, not becuase they were ancient. Even those few who had a genuine interest in Antiquity were drawn to it by an attraction tempered by utilitarian considerations. The Latin classics were considered above all as repositories of unusual information or moral teachings or as collections of fine phrases suitable for quotation or insertion into one's own writings. They were certainly not seen as the expressions of a great civilization. Roman remains were employed as building materials, or as architectural models, as can be seen for instance in the interior of Autun Cathedral and on the façade of that of Saint Gilles, or they could influence sculpture, as happened in France during the early thirteenth century, when art acquired there a new vitality through the study of ancient marbles. The inscriptions left wherever Rome had ruled were sometimes considered useful models, and as such were transcribed and imitated. Statues and sarcophagi were used again, while smaller antiques were often employed for various purposes. Roman cinerary urns were frequently turned into small stoups for holy water, as may be seen in more than one church in Rome, or could even be provided with a fresh inscription, as was the inscription in honour of St. Agnes and St. Alexander, placed there during the thirteenth century by Marco, Abbot of Santa Prassede. The ivory diptychs of the consuls became covers of gospel books or were even employed to record the dead of a particular church as happened for instance to the Boethius diptych of 487, on which were entered the names of the deceased of the church of Brescia. Sometimes the figures of the consuls carved on them were turned into saints or biblical characters, as happened in a diptych now at Monza, where they became King David and St. Gregory, and in one at Prague, where the consul was transformed into none other than St. Peter himself. Engraved gems went to adorn crowns and diadems, crosses, reliquaries and book covers. Thus the cross [of Lothair] given to the Minster at Aachen by the Emperor Otho III has an ancient cameo of the young Augustus; and also at Aachen the eleventh century ambo still displays some antique ivory tablets with decidedly pagan deities.

"One thing that must be borne in mind is that the Middle Ages did not envisage classical antiquity as a different civilization or a lost Paradise. Despite the difference in religion, until Petrarch medieval men failed to notice a fracture between the classical age and their own times. To them Frederick Barbarossa was as much a Roman Emperor as Augustus or Trajan and only differed from Constantine by his having been born several centuries after him. The medieval empire and that founded by Augustus were believed to be one and the same, and classical myth was often used for decoration in a religious setting. In fact the frequent warnings that pagan art was dangerous found little response even in ecclesiastical circles. During the early Middle Ages a vigorous classical revival took place under the Carolingians. This was in many ways a real renaissance, and the widest in scope ever witnessed before that which illuminated the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. . . ." (Roberto Weiss, The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity [1969] 2-3).