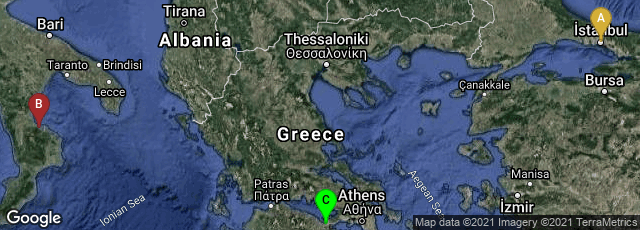

A: İstanbul, Turkey, B: Calabria, Italy, C: Korinthos, Greece

In "Books and Readers in Byzantium," a lecture given at the Colloquium on Byzantine Books and Bookmen held at Dunbarton Oaks in April 1971, and published as Byzantine Books and Bookmen (1975), Nigel G. Wilson provided a preliminary survey of book production and the book trade in the Byzantine empire, from which I quote. The links are, of course, my additions, and as usual, I have not included the footnotes:

"First, production and trade. A skeptic might well say that there is no evidence about the book trade, or even that there was no such thing. The skeptic is probably right in his belief, but instead of acceptiing it without discussion it may be worthwhile to analyze some factors which will have had an important effect on the production and circulation of books.

"The most obvious of these factors is the supply of writing materials. For much of our period it is clear that parchment was in short supply. There were, it seems factories, at Corinth, as Constantine Porphyrogenitus [De Administrando Imperio] tells us. In his commentary on this passage, however, Professor Jenkins saw here a reference to paper-making; but that looks to me like a slip of the pen, since I find it hard to imagine paper-making established as an industry in Byzantium as early as the middle of the tenth century. In Constantinople itself parchment was prepared at the Stoudios monastery, as we learn from the Magalai Katecheseis of Theodoros Studites. I suppose there must have been other factories elsewhere, but no evidence about them has come to my notice, nor do we know much about the two that can be identified. Parchment-makers are not mentioned as a guild in the Book of the Eparch. Are we to infer that there were not enough of them to make up a guild, or that they were regarded as a small section of the tanners whose affairs did not need to regulated by special provisions? At Corinth they are mentioned along with holders of imperial dignities, sailors, and purple-fishers as a group of people not liable to provide horses when requisitioned by the army. The context permits but does not require the inference that they were incorporated as a local guild.

"Another side of the picture is revealed when we find monks or men of letters unable to obtain writing materials. A journey might be necessary to find parchment, for in the tenth century St. Neilos was sent by his superiors to Rossano to buy some. But perhaps Italy was abnormal in this respect, since a great many surviving manuscripts believed to have been written in that area are either palimpsests or are made from parchment of extremely poor quality. On the other hand, there are signs that shortages were not confined to the poorer provinces. A schoolmaster in the capital in the twelfth century complains that writing material is hard to come by; I refer to John Tzetses, commenting on Aristophanes Frogs, 843, where the words used are τους χαρτας, which may be taken either as meaning parchment or as a generic term for paper and parchment. More than a century later we find Maximos Planudes writing to a friend in Asia Minor and asking him for parchment because the right quality is not on sale in his own neighborhood, which is presumably Constantinople. In the end, all he received was some asses' skins, which did not please him in the least. It may be that his friend refused to take the trouble to do what he asked, but it is equally possible that this inferior quality was sent because there was nothing else on the market.

"In the letters of the Patriarch Gregory of Cyprus there is a most interesting proof that the supply of parchment was seasonal; he says that he cannot have a volume of Demosthenes copied yet because there will be no parchment until the spring when the population begins to eat meat.

"Two more facts confirm the acute shortage. First, the yield of parchment from each animal was very low. A note in an Oxford manuscript (MS. Auct. T. 2.7) shows that two biofolia, equivalent to eight pages, might be expected from each animal; the text (fol. 419 verso) is εκοψαμεν δια δυο κατατομας προβ<ει>ες κ' και εποιησαν τετραδ<ι>α ι'. The low yield would be no surprise, because mediaeval animals were much smaller than their modern counterparts, which are the result of selective breeding since the eighteenth century. Secondly, it must have been a chronic shortage that forced booksellers into the unscruptulous habit of taking unwanted volumes, washing off the text, and using the parchment again. The canons of a church council forbid this practice in regard to biblical texts, and the canon lawyers Zonaras and Balsamon comment on it. Michael Choniates complains, no doubt with a good deal of rhetorical exaggeration, that the supply of books may fail altogether because whole shiploads of parchment have been sold to the Italians, and it is to be noted that this complaint was made long before the disaster of the Latin invasion of 1204, since it occurs in a text composed before his ordination.

"With regard to the supply of paper I can be much briefer. It was an inferior substitute, being less durable, but it had the obvious advantage that eventually it became a good deal cheaper. It was already in use in the imperial chancery as early as 1052, which is the date of an extant imperial chrysobull. But early paper manuscripts are not common, doubtless because most of them proved to be too perishable. Even if we allow that there was already a good supply of paper at that date, which I am inclined to doubt, it remains true that at least in the eighth, ninth, and tenth centuries there was no means of relieving the shortage of writing material.

"The supply of books is reflected in the prices they fetched. I have tried to show elsewhere [Reynolds & Wilson, Scribes and Scholars] that prices were high in relation to the salaries of civil servants, who were probably an important section of the reading public. Here I will explore the evidence a little more deeply. Stipends in the civil service seems to have begun at a lower level of 72 gold nomismata per annum, and in exceptional cases a man might receive as many as 3,500, but the average was probably a few hundred. The lowest book price I have found is three nomismata, paid in 1168 for MS Barberini gr. 319, a copy of the Gospels in small format written in the preceding century. Other prices are much higher, although it is not always possible to separate the costs of writing material and transcription. The prices are known of four of Arethas' books, and a reasonably consistent picture emerges from the following table:

Euclid (MS D'Orville 301), 387 folios, 22 x 180 mm., 14 nomismata.

Plato (MS E.D.Clarke 39), 424 folios, 325 x 225 mm., 13 nomismata for transcription, 8 for parchment

Aristotle's Organon (MS Urbinas gr. 35), 441 folios, 260 x 190 mm., 6 nomismata.

Clement of Alexandria (MS Paris. gr. 451), 403 folios, 240 x 190 mm., 20 nomismata for transcription, 6 for parchment.

"We may reasonably guess that the six nomismata paid for the Organon were for the parchment only, and the fourteen paid for Euclid were perhaps only for the transcription. The highest price, a total of twenty-six, is a respectable sum by any standards. A few other prices are known which confirm the picture of books as a commodity beyond the reach of the ordinary man. A copy of Chrysostom written in 939 (MS Paris. gr. 781) and consisting of 302 large folios cost seven nomismata, but what is included in the fgure seven is not clear from the world of the subscription. A metaphrastic menologion for January (MS Patmos 2345) written in 1057 carries a note saying that the scribe had been paid 150 nomismata for seven volumes, an average price of just over twenty-one. A liturgical book dated 1166 (MS Patmos 218) cost twelve nomismata, plus a further six for entering the musical notation. And in the thirteenth century we find the owner of a manuscript unable to afford the parchment eneded to replace some missing folios in MS. Vat. gr. 448.

"Given these limitations on production and ownership one has to consider what kind of trade can have existed in books. The key fact here is that booksellers are very rarely heard of. Agathias speaks of shops where one his contemporaries would attempt to engage in philosophical argument with the other customers. Michael Choniates speaks of booksellers in the passage cited already about the sale of parchment. But in general their activities remain a mystery. Until more evidence is found it may be best to assume that the trade in books was almost always in the form of secondhand transactions and special commissions given to professional scribes. . . . A fully developed book trade should not be postulated without special reasons; and so, for example, I believe that the suggestion by G. Zuntz that the manucript P of Euripides is a copy destined for the book trade has to be either unfounded or inadequately formulated.

"Similarly, the secondhand trade was limited. It should be noted that Michael Choniates, after losing his library in the sack of Athens in 1205, recovered some of his books and gave instructions to two of his friends to look out for a few particularly prized volumes that had not yet been found again: Euclid's Elements and Theophyact's commentary on the Pauline epistles, the latter being written in Michael's own hand. A similar case can be recorded from the fifteenth century: Constantine Lascaris recovered in Messina a text of Greek tragedy that he had lost eighteen years before; his own account of this coincidence is written on a spare leaf in the book, MS Madrid gr. 4677. It remains, of course, a question, whether these two coincidences should be regarded as typical experiences in the life of any Byzantine bookman." (pp. 1-4).