Between 1934 and 1942 grave robbers discovered the

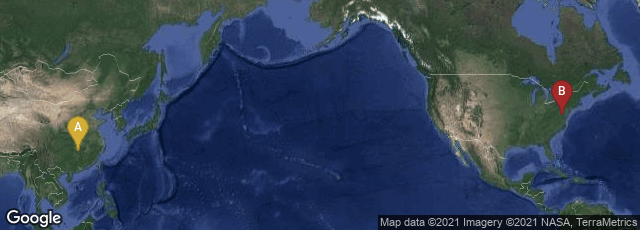

Chu Silk Manuscript in a tomb near Zidanku (literally "bullet storehouse"), east of

Changsha,

Hunan. Archaeologists later found the original tomb and dated it to around 300 BCE. In 1965 The manuscript was sold to art collector

Arthur M. Sackler, and it is preserved in the

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington, D.C. In significance for early Chinese culture it has been called "

a Chinese version of the Dead Sea Scrolls."

"Recent excavations of Chu-period tombs have discovered historically comparable manuscripts written on fragile

bamboo slips and

silk – the Chinese word

zhubo (竹帛 literally "bamboo and silk") means "bamboo slips and silk (for writing); ancient books". The Chu Silk Manuscript was roughly contemporaneous with the (c. 305 BCE)

Tsinghua Bamboo Slips and (c. 300 BCE)

Guodian Chu Slips, and it preceded the (168 BCE)

Mawangdui Silk Texts. Its subject matter predates the (c. 168 BCE) Han Dynasty silk

Divination by Astrological and Meteorological Phenomena." (Wikipedia article on Chu Silk Manuscript, accessed 9-2020).

Having passed into American hands at a time when the Chinese had few export controls for cultural objects, in recent years pressure has been growing for the manuscript to return to China either through donation or purchase. On June 8, 2018 Ian Johnson

published an article in The New York Times on this controversy , referring to a monaograph by the Chinese historian and archaeologist Li Ling, entitled

The Chu Silk Manuscripts from Zidanku, Changsha (Hunan Province): Vol. 1. This was published by the Chinese University of Hong Kong Press in 2019 and in the U.S. by Columbia University Press in 2020, but it appears that Mr. Johnson may have seen a pre-publication copy. From his article published on June 8, 2018 I quote a few summary paragraphs:

"For decades, the ancient document, known as the Chu Silk Manuscript, has fascinated people seeking an understanding of the origins of Chinese civilization. But it has been hidden from public view because of its fragility — and the uncertain circumstances by which it ended up in the United States.

"Now, a prominent Chinese historian and archaeologist [Li Ling] has pieced together its remarkable odyssey in a meticulously documented analysis that has caused a stir in the rarefied world of Chinese antiquities and raised broader questions about collectors who profit from pillaging historic sites.

"The 440-page study traces the provenance from tomb raiders who discovered it during World War II, to an antiques dealer whose wife and daughter died fleeing Japanese troops, to American spies who smuggled it out of China and finally to several museums and foundations in the United States."