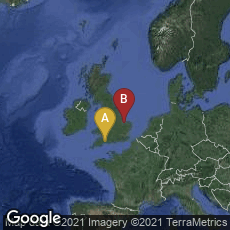

A: Lyme Regis, England, United Kingdom, B: King's Lynn, England, United Kingdom

On March 28, 2014 British antiquarian bookseller Justin Croft drew the attention of the Ex-Libris newsgroup to a blog post of his dated October 26, 2012 in which he discussed the earliest surviving paper record in England, the "Red Register" of King's Lynn, a register of deeds enrolled in the seaport town of King's Lynn from 1307 to 1372. Croft had the opportunity to examine the book when he visited the borough archives still housed in the King's Lynn Town Hall.

Croft's post struck a cord with me when I searched this database and discovered that my entry for the first use of paper in England was a pathetic undocumented single sentence that said, inaccurately, "The first recorded use of paper in England was in 1309." This entry, numbered 314 in the database, was one of my earliest short notes, written when I began attempting to broaden the scope of the data beyond the history of computing, networking and telecommunications, to cover the history of media, for the simple present tense timeline in my 2005 printed book From Gutenberg to the Internet. That timeline was an expansion of the timeline that I wrote for my printed book Origins of Cyberspace (2002). In 2005 I had no expectation that the project would become a website, or that it would reach anywhere near the extent it had reached in 2014. And though I had revised, expanded, or otherwise corrected many of those original overly brief and unsubtantiated notes since 2005, for some reason this relatively meaningless entry had been left essentially in its original state. Therefore I took the opportunity that Croft's post offered to expand this entry. Croft wrote:

"In the early fourteenth century England’s writers habitually wrote, as we all know, with quill pens on sheets of parchment or vellum. And that’s true of writers in a variety of fields: in the church, the law courts, or in royal and local government. Here in Lynn, in 1307 we find a medieval writer (or probably writers) writing on quires of paper with the clear intention of binding them up as a book. The paper could not, of course, have been English: the first recorded English paper mill dates from only the 1490s, when a Hertford paper maker supplied paper to the printer William Caxton.

"It was only after I returned home to Faversham (which coincidentally has a pretty mean collection of medieval charters) that I realised just how early the Lynn paper book was. In fact, consulting the endlessly-useful classic by Michael Clanchy From Memory to Written Record, I found that: ‘The earliest records made in England on paper come most appropriately from major seaports: a register from King’s Lynn beginning in 1307 and another from Lyme Regis in 1309’.

"The King’s Lynn Red Register is then, the earliest surviving English paper book. I realise that, had I been paying attention, I would have noticed it even has its own blue plaque outside the town-hall, though it doesn’t tell us why it’s important.

"It’s a common (and fair) assumption that paper books have something to do with printing. Books are printed on paper. There are a few black-tulip exceptions, usually very early (a few copies of the Gutenberg Bible and other incunables, including Caxtons, and of course a few copies of the wonderful Kelmscott Chaucer and other private press books; late revivals of vellum printing). There’s also a co-incidence of chronology: paper making, especially in England, takes off with the advent of printing. Conversely, we tend to think of medieval manuscripts as written on parchment or vellum.

"On reflection I can now think of several examples of English medieval manuscripts on paper, mostly urban or legal registers from the fifteenth century (there’s even one here in Faversham). A few date from the period before printing, but very few from the fourteenth century. That makes the 1307 Red Register at Lynn truly remarkable.

"It speaks of a confident leap-of-faith on behalf of the town government to make an important civic record on a material with such a short track-record in practice. Of course we know that Chinese and Islamic cultures used paper long before, but the first paper mills in Europe were not active before the 1270s (in Italy; where else?). Urban records were not mere shopping lists: they were the documents used by powerful ruling elites to protect the data which allowed them to carry out their day to day business in the knowledge that they were acting correctly and lawfully. Town documents were jealously guarded and treated with all the care and respect that a major business corporation would use to maintain and back-up its databases. That is one reason why medieval town records have such a good rate of survival.

"To experiment with paper as a record-keeping technology was a brave and forward-looking move in 1307. Probably before its time, since it didn’t catch on for so long. Paper would turn out to have all kinds of advantages over parchment: it can be less bulky, it allows for much more rapid writing in new, faster hands, and ultimately it would become cheaper. By 1500, except for deeds and charters, paper would become dominant in record-keeping of all kinds. Perhaps most significantly, in the long run, it provided a perfect surface for printing."

In Pragmatic Literacy, East and West 1200-1330, edited by R. H. Britnell (1997) Geoffrey Martin wrote in a chapter entitled "English Town Records", "The relatively high cost of parchment seems to have limited the scope of personal archives. It was some time before paper became a cheap alternative, and its use was limited in the towns before the end of the fifteenth century. The earliest example is a register of deeds enrolled at King's Lynn, from 1307, followed by the Husting court book of Lyme Regis in Dorset, a similar register begun 1308. The so-called Little Red Book of Bristol and the Red Paper Book of Colchester, a paper volume also original bound in red leather, are other examples from the first and second halves of the century respectively." (p. 130.)

Perhaps it is not coincidental that both of these early English registers on paper were created in seaport towns in which trade must have been very active with continental regions where paper was in production. By the twelfth century paper was being produced in the Iberian peninsula and in Italy. Paper production did not reach France or Germany until mid to late 14th century. Therefore it is likely that the paper used for both the King's Lynn and Lyme Regis registers came from Italy or Spain. The first papermill in England arrived very late compared to continental developments. John Tate operated the first English papermill from 1496 to 1507, and the first book printed in England on paper made in England was printer Wynkyn de Worde's first English edition of Bartholomaeus Anglicus's De proprietatibus rerum in the English translation of John Trevisa. According to the ISTC, this undated edition was issued "circa 1496."

The Red Register of King's Lynn was transcribed by Robert F. Isaacson and edited by Holcombe Ingleby for publication in King's Lynn in 1922 in a 2 volume work entitled appropriately, The Red Register of King's Lynn. Consisting of mainly deeds and wills, it provides invaluable records of an important town in the fourteenth century. However, from the book history standpoint the key element of this register is its early use of paper as a recording medium.