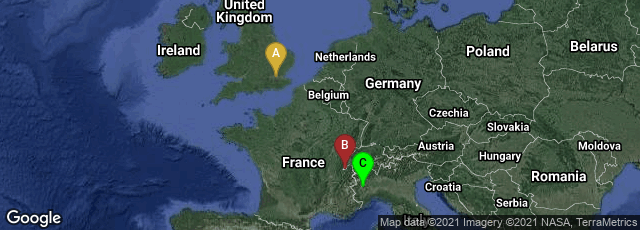

A: London, England, United Kingdom, B: Centre-Plainpalais-Acacias, Genève, Genève, Switzerland, C: Torino, Piemonte, Italy

In 1842 Italian mathematician and politician Luigi Federico Menabrea published "Notions sur la machine analytique de M. Charles Babbage" in Bibliothèque universelle de Genève, nouvelle série 41 (1842) 352–76. This was the first published account of Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine and the first account of its logical design, including the first examples of computer programs ever published. As is well known, Babbage’s conception and design of his Analytical Engine—the first general purpose programmable digital computer—were so far ahead of the imagination of his mathematical and scientific colleagues that few expressed much curiosity regarding it. Babbage first conceived the Analytical Engine in 1834. This general-purpose mechanical machine— never completely constructed—embodied in its design most of the features of the general-purpose programmable digital computer. In its conception and design Babbage incorporated ideas and names from the textile industry, including data and program input, output, and storage on punched cards similar to those used in Jacquard looms, a central processing unit called the "mill," and memory called the "store."The only presentation that Babbage made concerning the design and operation of the Analytical Engine was to a group of Italian scientists.

In 1840 Babbage traveled to Torino (Turin) Italy to make a presentation on the Analytical Engine. Babbage’s talk, complete with charts, drawings, models, and mechanical notations, emphasized the Engine’s signal feature: its ability to guide its own operations—what we call conditional branching. In attendance at Babbage’s lecture was the young Italian mathematician Luigi Federico Menabrea (later prime minister of Italy), who prepared from his notes an account of the principles of the Analytical Engine. Reflecting a lack of urgency regarding radical innovation unimaginable to us today, Menabrea did not get around to publishing his paper until two years after Babbage made his presentation, and when he did so he published it in French in a Swiss journal. Shortly after Menabrea’s paper appeared Babbage was refused government funding for construction of the machine.

"In keeping with the more general nature and immaterial status of the Analytical Engine, Menabrea’s account dealt little with mechanical details. Instead he described the functional organization and mathematical operation of this more flexible and powerful invention. To illustrate its capabilities, he presented several charts or tables of the steps through which the machine would be directed to go in performing calculations and finding numerical solutions to algebraic equations. These steps were the instructions the engine’s operator would punch in coded form on cards to be fed into the machine; hence, the charts constituted the first computer programs [emphasis ours]. Menabrea’s charts were taken from those Babbage brought to Torino to illustrate his talks there"(Stein, Ada: A Life and Legacy, 92).

Menabrea’s 23-page paper was translated into English the following year by Lord Byron’s daughter, Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace, daughter of Lord Byron, who, in collaboration with Babbage, added a series of lengthy notes enlarging on the intended design and operation of Babbage’s machine. Menabrea’s paper and Ada Lovelace’s translation represent the only detailed publications on the Analytical Engine before Babbage’s account in his autobiography (1864). Menabrea himself wrote only two other very brief articles about the Analytical Engine in 1855, primarily concerning his gratification that Countess Lovelace had translated his paper.

Hook & Norman, Origins of Cyberspace (2002) No. 60.

"Without being Worked out by Human Head & Hands. . . ."

While she was working on her translation, on July 10, 1843 Ada Lovelace composed a letter to Babbage concerning her notes to Menabrea's paper on programming Babbage's Analytical Engine. This autograph letter, preserved in the British Library (Add. MS 37192 folios 362v-363), includes the following text:

"I want to put in something about Bernouilli's Numbers, in one of my Notes, as an example of how an implicit function may be worked out by the engine, without having been worked out by human head & hands first. Give me the necessary data and formulae."

The letter is notable for suggesting that Ada's knowledge of mathematics was limited, and that she may have mainly contributed poetic language to her annotations of the English translation of Menabrea's key paper, while incorporating mathematical examples written by Babbage. Because of Ada's fame as Byron's daughter, and her social position as the Countess of Lovelace, Babbage hoped that Ada's translation and annotation of Menabrea's paper would help promote building the Analytical Engine.

In October 1843, Ada Lovelace's "Sketch of the Analytical Engine Invented by Charles Babbage . . . with Notes by the Translator" was published in Scientific Memoirs, Selected from the Transactions of Foreign Academies of Science and Learned Societies 3 (1843): 666-731 plus 1 folding chart. At Babbage’s suggestion, Lady Lovelace added seven explanatory notes to her translation, which run about three times the length of the original. Her annotated translation has been called “” (Bromley, “Introduction” in Babbage, Henry Prevost, , xv). As Babbage never published a detailed description of the Analytical Engine, Ada’s translation of Menabrea’s paper, with its lengthy explanatory notes, represents the most complete contemporary account in English of this much-misunderstood machine.

At Babbage’s suggestion, Lady Lovelace added seven explanatory notes to her translation, which run about three times the length of the original. Her annotated translation has been called “the most important paper in the history of digital computing before modern times” (Bromley, “Introduction” in Babbage, Henry Prevost, Babbage’s Calculating Engines, xv). As Babbage never published a detailed description of the Analytical Engine, Ada’s translation of Menabrea’s paper, with its lengthy explanatory notes, represents the most complete contemporary account in English of this much-misunderstood machine.

"Babbage supplied Ada with algorithms for the solution of various problems, which she illustrated in her notes in the form of charts detailing the stepwise sequence of events as the machine progressed through a string of instructions input from punched cards" (Swade, The Cogwheel Brain, 165).

These were the first published examples of computer “programs,” though neither Ada nor Babbage used this term. She also expanded upon Babbage’s general views of the Analytical Engine as a symbol-manipulating device rather than a mere processor of numbers, suggesting that it might act upon other things besides number, were objects found whose mutual fundamental relations could be expressed by those of the abstract science of operations. . . . Supposing, for instance, that the fundamental relations of pitched sounds in the science of harmony and of musical composition were susceptible of such expression and adaptations, the engine might compose elaborate and scientific pieces of music of any degree of complexity or extent (p. 694) . . . Many persons who are not conversant with mathematical studies, imagine that because the business of the engine is to give its results innumerical notation, the nature of its processes must consequently be arithmetical and numerical, rather than algebraical and analytical. This is an error. The engine can arrange and combine its numerical quantities exactly as if they were letters or any other general symbols; and in fact it might bring out its results in algebraical notation, were provisions made accordingly (p. 713).

Much has been written concerning what mathematical abilities Ada may have possessed. Study of the published correspondence between her and Babbage is not especially flattering either to her personality or mathematical talents: it shows that while Ada was personally enamored of her own mathematical prowess, she was in reality no more than a talented novice who at times required Babbage’s coaching. Their genuine friendship aside, Babbage’s motives for encouraging Ada’s involvement in his work are not hard to discern. As Lord Byron’s only legitimate daughter, Ada was an extraordinary celebrity, and as the wife of a prominent aristocrat she was in a position to act as patron to Babbage and his engines, though she never did so.